This Time Better Be Different - Redux

Corp. credit remains unstoppable, but it's not a bubble; until it turns, it'll be a helluva battle between bulls & bears; so far the path to where we are now has been different; the end result? Dunno.

Back in July of this year I wrote a piece titled “This Time Better Be Different”. The gist of the article was the excerpt below:

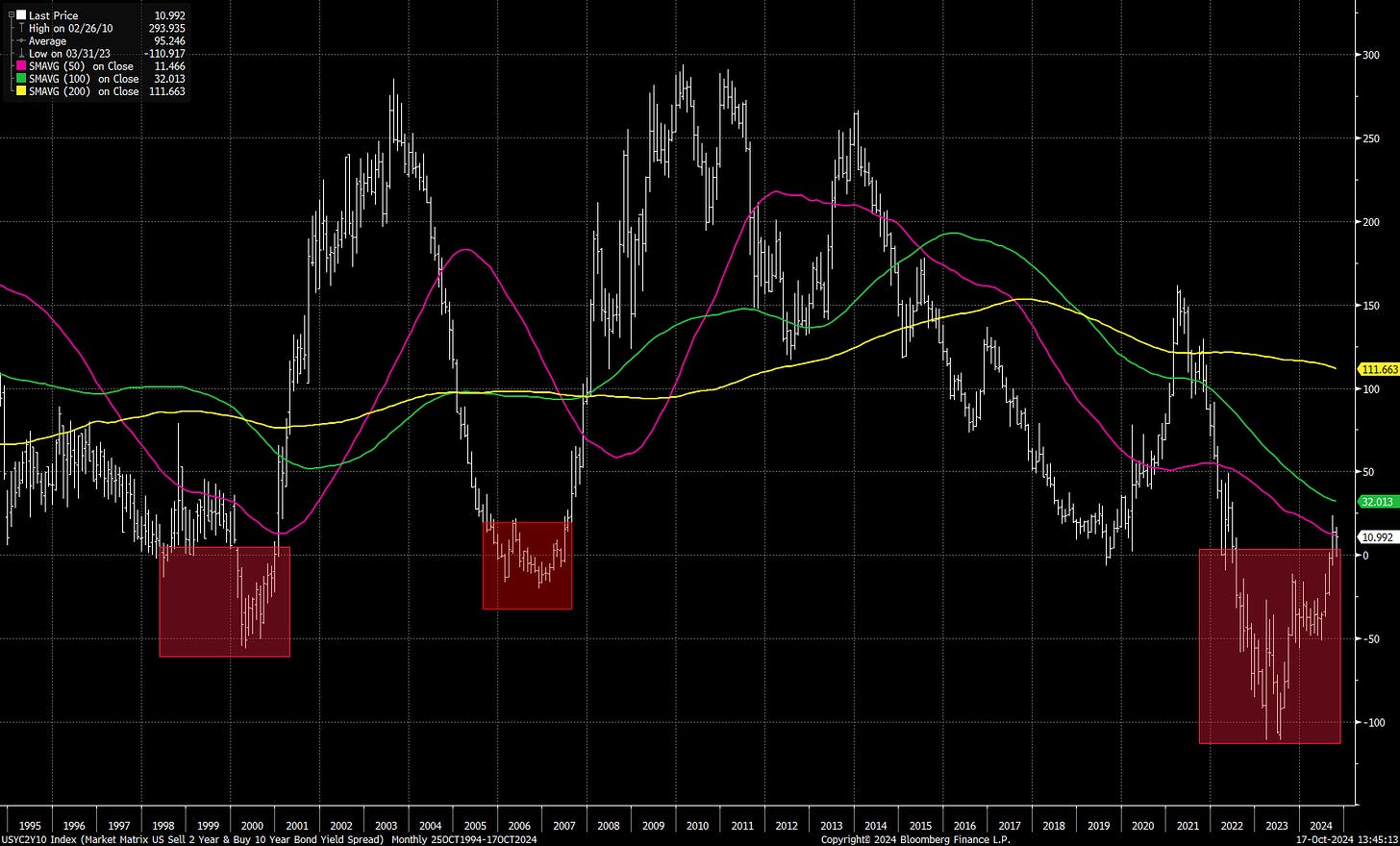

“The 2s10s inversion which began in June of 2022 is now the longest since the Sep. 1978 - Dec. 1981 stretch. Considering the inflation/rates chaos of those years, it is fair to say that the duration and depth of the current inversion is different. After the last two more recent inversions (‘99-’00 and ‘06-’07), credit crisis and market collapses followed shortly after the Federal Reserve cut rates reversing a sustained period of rate hikes (chart below). Keep that in mind, because all those who are bulled-up on a coming series of rate cuts are 100% betting that “this time is different”. I am not saying it can’t be, but it’s worth/necessary keeping one’s antennas up. If it is not different this time, corporate credit spreads should be our tell before a whole lot of stuff implodes.”

Every year, the September and January issuance periods are critical tells of the state of the credit markets, and the first day of the September surge was one for the history books. That day the corporate bond market printed the second largest issuance day ever, and in that piece I laid out the importance of a successful September bond sales surge for corporate credit and for stocks. As the month came to a close, it did not disappoint: corporate issuance tallied $246B (just $2B shy of the $248B printed in September 2020 and 2021), and newly announced stock buybacks totaled $100B. By my records, only February of this year had a higher combined number - $247B and $167B respectively.

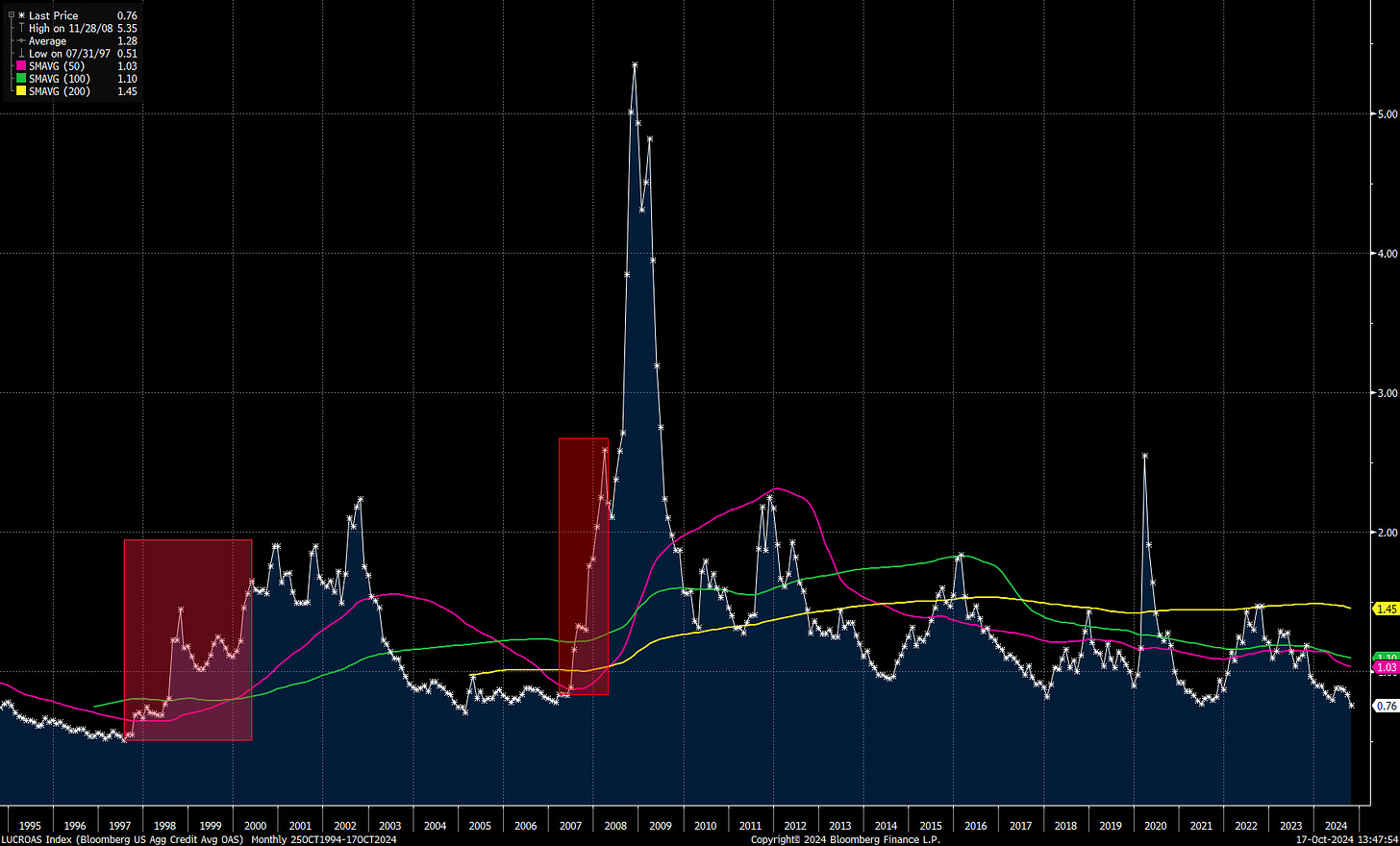

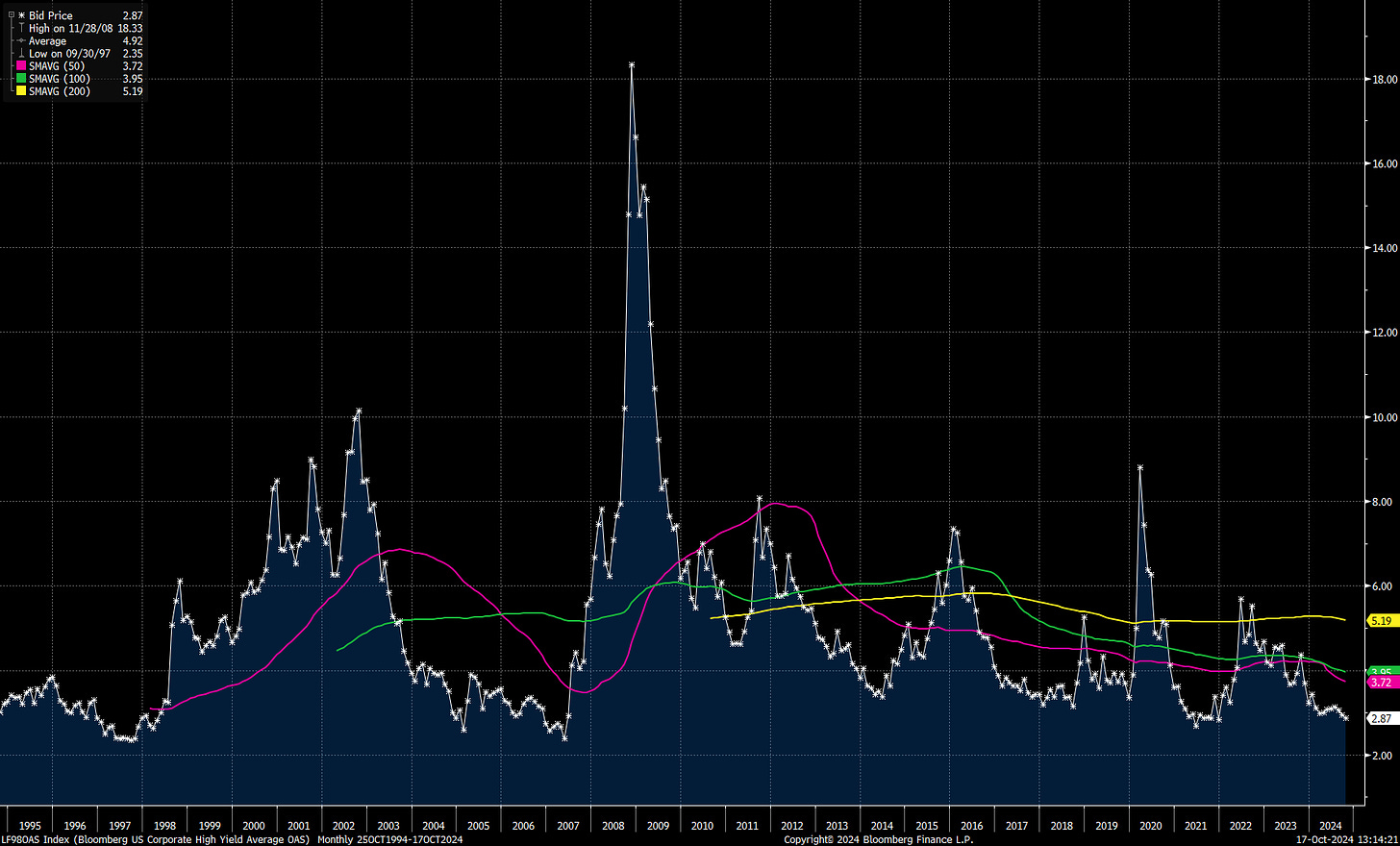

More importantly, in light of the re-steepening of 2s10s after an inversion which set all time records for its length and depth, I suggested focusing on the behavior of risk spreads given that the last two credit crisis were tipped off by a significant widening shortly after the 2s10s had re-steepend. So, what happened since then? Both Investment Grade and High Yield spreads are now tickling some of the best levels in decades. (Charts below).

At risk of jinxing the whole thing, it’s fair to say that credit markets have indeed sounded the all clear for the rest of the year and stocks are likely to follow. Regardless of geopolitics and/or elections-related wild gyrations in stocks (equities do feel pretty/complacent going into earnings season and the elections), companies’ coffers are stuffed with cash available for buybacks and, for my money, any air pocket in equities will be yet another proverbial opportunity to “buy the dip” and wait for buyback desks to decide when yet another correction will end.

Given my own complacency (at least for the longer term) skeptical readers might be tempted to fade my enthusiasm, so I may as well feed them more fodder by addressing a topic that has popped up more and more frequently on my Twitter timeline (@FZucchi if you care to follow): are the razor thin risk spreads in corporate bond prices a sign of a credit bubble? Will it inevitably burst? Haven’t we seen this movie back in 2007? The one-word answers are: No, Yes and No. To explain them I’ll take the last question first.

The credit meltdown of the Great Financial Crisis began way before equity markets even noticed, let alone focused on it. The first blow came in August 2007 when BNP Paribas gated three asset-backed-securities mutual funds for lack of liquidity. By September, Prime Money Market funds (i.e. institutional money market funds) were having trouble pricing assets; next the weekly auctions of Municipal Auction Rate Securities, which in those days were one of the most liquid institutional money-market-like products, were grinding to a halt (they would fail completely by Feb. ‘08, and more than $300b of investors capital would remain locked up for more than a year). Compare with how credit markets are behaving now, with record setting issuance, IG and HY credit spreads at decade tights, and even the leveraged loans market (riskier credits than HY bonds) near peak levels. In short, the current “movie” on the state of credit could not be any more different than the one in September ‘07.

If credit markets are in such great shape, are they in a bubble? The answer is no for a couple of reasons. First, bonds are still the domain of institutions, and bubbles are more often than note driven by the animal spirits of retail investors; the average trade size in a corporate bond is $2-3M; the market as a whole is rather illiquid, with roughly $50b of average daily volume (just Nvidia can do that in one day); and bid/ask spreads are prohibitively wide for trading purposes. Most individuals are involved in corporate bonds through mutual funds, CEFs, ETFs, etc., and they tend to own these funds for the stream of income, not for trading or capital gains. As a corollary, a plain vanilla bond has no upside above par, so yes, it can be bought or sold at a mispriced level relative to its yield/risk, but the price cannot disconnect from its liquidation value like other asset classes can.

Second, the corporate bond market is about as procyclical as they come,1 meaning that when risk is low (i.e. spreads are tight), pension funds, endowments and credit funds (many of which are leveraged) want to buy. These buyers are not particularly price sensitive, and, even if they were, they often do not have much choice, because if they have funds on hand, they have to put it to work in order to earn the returns needed to match their liabilities. On the flip side, when risk rises buyers disappear, and some may even turn into sellers if the leverage goes against them. Hence the “bids-wanted” characteristic of a credit crisis.

These two aspects of the corporate bond market (there are others, but that’s for another time) make it nearly impossible for this market to go into a “bubble”. Unlike stocks or commodities, where various buyers (not to mention short sellers caught on the wrong side of the trade) can show up at different times and drive prices to insanity until things reverse for no reason or any reason, credit market participants are driven by the bonds’ broad risk profile (as reflected in risk spreads), not by momentum, speculation or other “bubbly”/emotional behavior.2

So why do I think that this non-bubble will burst at some point? Because credit cycles always end, and when they do end, they end very badly. What ends a credit cycle is the trillion-dollar question.

The last two credit cycles ended following the re-steepening of 2s10s inversions. There is a never-ending chicken-or-the-egg debate as to whether inversions foretell recessions/credit crisis (the most common narrative), or whether inversions cause credit crisis and hence recessions (my preferred take). I won’t go down that rabbit hole because it really serves no purpose. I rather remain focused on whether an unwind is in the offing, and risk spreads have nailed the incoming collapses in ‘98 and ‘07 well before stocks and most other asset classes. (You can match up the red boxes in the first chart and the one below to see how helpful it would have been to heed the message).

As reference, Investment Grade risk spreads above 150bps and High Yield spreads above 500bps are the levels where credit demand starts drying up. How fast spreads get to those levels (the speed of a move in credit is as, if not more, important as the size and the levels), and what’s happening in the macro backdrop once they get there, usually dictates what happens after that.

And that takes us where we are today: despite the double whammy of the 2s10s re-steepening combined with the first Fed rate cut, (you can read more about the possible implications of that here), for now risk spreads are 100% dismissing the double whammy, and all the other dangers out there - geopolitical, elections, the commercial real estate meltdown, and the gamification (h/t Peter Atwater on Twitter) of many asset classes.

So, are things different this time? I don’t know if they will continue to be different, but there is no arguing that, so far, they have been and continue to be.

Over the last 10+ years this has been exacerbated by investment banks pulling back from holding inventory, i.e. being “market makers”, during times of stress.

The same is NOT true of the Treasury bills/bonds complex where the size and liquidity of the market, together with all sorts of leveraged derivatives allow for speculation galore. Yes, I am old enough to remember the Long Term Capital Management meltdown.