I have twitted often about the importance of the shape of the 2-10 yield curve, and there is no lack of financial and fintwit commentary on its ramifications. Rather than repeating myself over and over in “280 characters” as to why I believe it matters, here is my take with some data to back it up. But first, one paragraph to explain in what context an “inverted yield curve” (i.e. 2y Treasury yield higher than the 10y Treasury yield) does NOT matter much.

If an inverted yield curve simply foresees a coming recession, it is not a big deal. Recessions are not “healthy” (as many like to suggest), especially if one’s source of income is directly affected. But recessions are an inevitable part of our economic system, the system is set up to absorb them, and, once they end, we can look forward to more prosperity.

Now, for the scarier bit, i.e. why our current financial structure may not be equipped to endure a prolonged period of inverted yield curves. I will use the 2-10 curve as the default, but the same rationale would apply if both terms were less than 2 and 10 years. And one last disclaimer: the figures I show below are very much approximations, but for purposes of this article, +/- $100b probably would not make much difference.

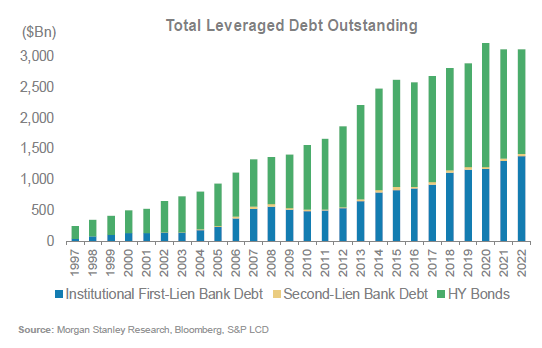

US companies have approximately $8T of Investment Grade (IG) debt outstanding, and $3T of High Yield (HY) debt.

The bulk of this debt is owned by pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, foundations, and foreign investors.

Based on data from PIOnline.com, approximately 2/3 of this debt is owned through “alternative investments” vehicles, i.e. leveraged credit funds, private credit funds, direct lending funds, etc. I will refer to them as LCFs.

LCFs invest their equity capital to purchase corporate bonds, and they leverage up by borrowing additional money on a relatively short-term basis (generally 2 years or less) to purchase more longer-term corporate bonds. If all goes well, this allows them to juice up their returns. More importantly, if all goes well the LCFs will have every reason to be buyers when the original bonds roll-over or new bonds come to market. Examples of successful leveraged investments are shown on the 1st and 4th lines of the table below.

These are actual bond issues from 2018. The 1st line is a BB+ junk bond, while the 4th line is an A+ IG bond. I have assumed that the LCFs lever up a “reasonable” 3x; the 1st and 4th line show the pro-forma results given a 0.55% positive shape of the 2-10 yield curve at the time the bonds were issued. Bottom line: an LCF could have invested $25M, added an additional $75M of margin debt at the 2y rate + the risk spread (I’m guestimating 50bps), and, thanks to the bond coupons of 4.8% and 3.55%, the LCFs would have earned an annual ROE of 10.95% and 5.95%. All good so far.

Now look at the 2nd and 5th lines; same bonds, same coupon, same leverage, but the yield curve is inverted by 0.7%; the base cost of borrowing for 2yrs has jumped to 3.5% making the total margin cost 4%. The ROE for the bonds drops to 7.2% and 2.2% respectively. Positive, but much less appealing given the risks being taken.

While a surface view of these returns might tempt a reader to ask “what’s the big deal?”, a really big – potentially systemic – “deal” lurks below the surface. As Guy LeBas (Chief Fixed Income Strategist at Janney) pointed out to me, in any given year approximately 20% of outstanding bonds mature within 12-36 months. Going with the mid-point of 24 months and using the total current outstanding debt ($8T of IG and $3T of HY), refinancings for 2023 and 2024 will be about $1T per year. Also, an additional $500-700b of new debt is issued every year (this is a very rough estimate based on the chart below).

The last bit of critical data (also from PIOnline.com) is that large bond buyers allocate about $175-200b of new money to the alternative investment funds used to buy bonds.

So here is the potentially BIG problem:

· Given $1T of refinancings, plus another $600b of new debt, credit buyers need to show up with about $1.6T to keep things rolling;

· If leveraged 3x, the $175-200b allocations of new money would yield buying power of just under $800b, and if the entire $1T of maturing bonds is rolled into new issues, all is well.

But what happens if the buyers decide that, with an inverted yield curve, taking on 3x leverage does not makes sense? What happens if the allocations of new money to LCFs drop? What happens if there is not enough cash to roll debt, to finance companies’ operations, or, God forbid! (tic), fund stock buybacks?

I hesitate to bring up ’00 -’03 or ’07 -’09. The backdrop right now is quite different. The internet bubble was a once in a life-time form of insanity, which included the Worldcom and Enron bankruptcies, two of the most spectacularly fraudulent credit implosions ever. The GFC was a close second in terms of “madness of crowds”, with the added accelerant that the credit meltdown was centered in the banking and mortgage area, which damn near risked a complete collapse of the financial system. But, on the flipside, both those events were indeed preceded by prolonged inversions of the 2-10 yield curve and a drying up of money flowing into credit.

I suspect that if the yield curve damages the credit markets, this time around the outcome will be better than the last two crisis, but significantly worse than what is priced into credit risk spreads and equities. Markets will likely face a rash of restructurings among the weaker companies, and significantly higher coupons even for IG credits. Bondholders will lose money, a circumstance they are rarely prepared for. Equity buybacks will take second chair to balance sheets deleveraging. In sum, the episode will be bad enough that the financial stresses will spill into the everyday economy.

It is not yet predetermined that a credit accident must or will happen. The curve inversions that preceded the internet bust and the GFC went on for 10 and 12 months respectively. The current spell is only in its second month. There is time to prepare. Credit risk spreads, new bond-issuance volumes/pricing, continued allocations of new money to alternative credit vehicles, the tone of trading of new issues in the secondary market, bond ratings upgrades/downgrades, and the ability of banks to offload M&A loans, should all be important early tells if trouble is lurking.

Coincidentally, all these measures will be in clear display starting a few days after Labor Day, when the most important window of corporate bond issuance will open up and last for most of September. A successful bond-sales surge would go a long way toward giving credit markets breathing room until the end of the year, while a flop would be another body blow to credit and equities, and a red flag for things to come.

Very interesting. Thank you for the insights and education in to how credit markets work.

Great writeup -- it's always the liquidity transformation dependent on short-term paper that seems to get us. Any idea how much issuance you'd like to see to feel comfortable? And anywhere you'd track on bbg / elsewhere?